Versione italiana

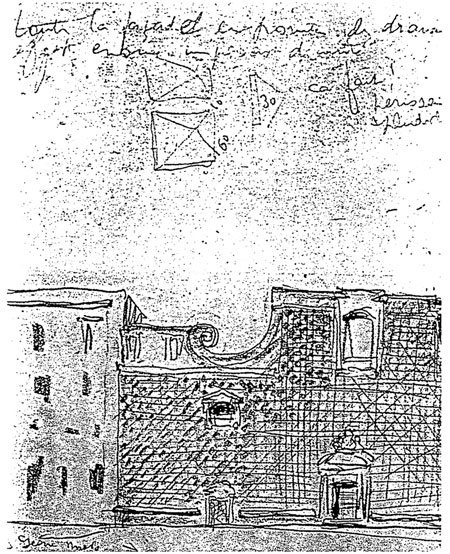

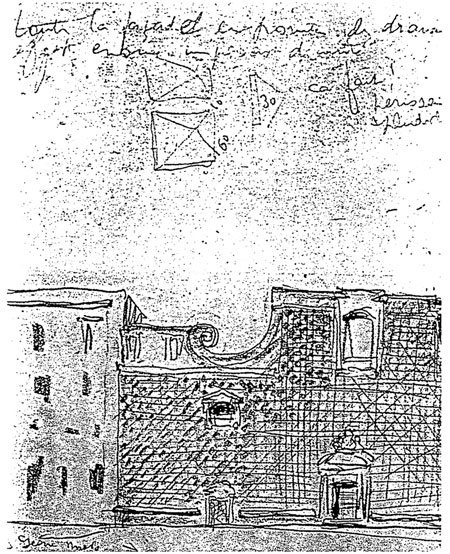

Church of Gesù Nuovo, Naples. Partial view of the diamond-pointed rustication (photo A. Acocella)

During the second half of the 14th century, the influence of the by now famous Florentine palazzi began to be felt in other Italian cities, where wealthy residences with rusticated façades were built, some boasting unusual and original rusticated motifs. Examples of the latter include the geometrical, diamond-pointed rustication of Bologna’s famous Palazzo Sanuti (later Bevilaqua) and Ferrara’s Palazzo dei Diamanti. However, the number one city for this type of rustication is, in fact, Naples: fine examples include the basement storey of Palazzo Sicola (no longer standing) and, in particular, Palazzo Sanseverino (1455-1470), built by Novello di Sanlucano: these Neapolitan buildings led the way in the employment of diamond-pointed (flat-topped pyramid) rustication. Naples’ avant-garde Renaissance creations, in turn, were to a certain degree directly influenced by the “royal rustication” characterising the basement escarp of the Castel Nuovo towers.

The brown-coloured, rusticated piperno ashlars used in the Sanseverino family’s residence were “recycled” after the destruction of the building, and employed in the construction of the new façade of New Christ Church (Gesù Nuovo) in 1584, situated in the square of the same name. The church and the rusticated ashlars were to be photographed and sketched, to be included in Le Corbusier’s famous Carnets d’un Voyage d’Orient) documenting his visits to, and studies of, the sites of ancient Mediterranean civilisations. The Swiss architect notes the size of the ashlars: 60 x 60 cm. at the base; 30 cm. the height of the vertex. The photos, of selected details of the rustication, provide a foreshortened perspective; the dynamic photographic approach is particularly striking, with shots taken from a grazing angle looking upwards, with the network of diamond-pointed ashlars seen from a diagonal perspective, further proof of Le Corbusier’s professed interest in the effect and significant plastic value of Italian architecture.

Church of Gesù Nuovo, Naples. Sketch by Le Corbusier taken from his “Carnet d’une Voyage d’Orient”

While Naples can be considered the leader in the Renaissance employment of diamond-pointed rusticated facing, Ferrara possesses the best, most refined example of a building “ennobled” by façades completely clad in diamond-pointed rusticated ashlars. In the Estense family’s hometown, dominated by the use of red brick, the world of stone architecture insinuates its way into the urban fabric via the waterways that bring limestone and the most valuable of Italian marbles in from Verona and Istria.

The Palazzi dei Diamanti, perhaps the town’s finest building, boasts a splendid monumental façade of diamond-pointed ashlar: the building was commissioned by Sigismondo d’Este, and begun by Biagio Rossetti in1493. The specific reference to rustication made by a Modena chronicler visiting Ferrara in 1496, confirms that it was Rossetti’s creation (at that time he was managing construction work, aided by Gabriele Frisoni of Mantua); the visitor was already able to admire the escarped, diamond-pointed façade that year.

Corner detail of Palazzo dei Diamanti in Ferrara (photo A. Acocella)

The dressing and laying of the cladding ashlars continued, from 1503 onwards, under the management of Girolamo Pasini and Cristoforo of Milan, and work on the two main rusticated façades was not really completed until 1567. The resulting composition was not of a vertical nature as in the Florentine models, but based on a horizontal rhythm more characteristic of the Renaissance buildings of northern Italy.

The diamond-pointed rustication is designed to give the masonry a uniquely elegant appearance: a refined chiaroscuro effect created by the shape of the ashlars, only slightly attenuated by the corner parastatas decorated with candelabra motifs and horizontal cornices. The two façades consist of the careful arrangement of thousands of pointed ashlars of white Verona limestone and the occasional reddish ashlar. One can easily imagine the considerable difficulty the builders must have had in finding and transporting so much stone from afar at that time; however, the desire for the rarest and noblest stone, rather than for the more readily available and far less expensive brick, has been a constant factor in the history of construction.

A close examination of the ashlar-work during recent studies has identified certain unique details. For example, there is a gradual shift in the axis of the pyramids (diamonds): in the rusticated basement section, the vertices are noticeably angled downwards; in the central section, they are perpendicular to the surface plane of the façade; then in the upper section of the façade, they are once more inclined, this time in an upwards direction. The suggestion that this may be a chance event or a technical imperfection is, however, denied by the fact that at you get closer to the corner parastatas, the diagonals between the vertices of the pyramids follow a regular, curvilinear pattern, whereas this becomes less evident as you move away from the corner. It appears highly unlikely that Rossetti and Frisoni were unaware of this phenomenon. These almost imperceptible optical effects contribute significantly to the overall appearance of the façades, as they prevent the rusticated wall from appearing figuratively static, rendering it more intriguing and vibrant from an aesthetic point of view.

The façade wall is sub-divided into four compositional horizontal layers, while its vertical aspect is characterised by the presence of candelabras sculpted by Gabriele Frisoni, with delicately modelled figures (in keeping with the traditional, exquisite corner piers that often flank the red-brick walls of buildings in Ferrara) employed both as decorative lesenes, and as the boundaries of the diamond-pointed ashlars of the corner line (thus solving the problem of angular intersection). The continuous escarp, which ends in a protruding, bull-shaped cornice, represents the transposition of the traditional terracotta basement design used in Ferrara’s buildings; this is followed by the perfectly vertical ground-floor wall featuring openings in the lower half, and ovolo mouldings with architraved fasciae in the upper section. The latter, which acts as a string course and supporting element, features the upper-floor windows surmounted by a triangular tympanum; the cladding extends around the windows until it meets a “neutral fascia” separating the ashlar work from the cornice.

Facade details of Palazzo dei Diamanti in Ferrara (photo A. Acocella)

Compared to the Florentine models in their archaeological phase, the sharp rusticated facing designed by Biagio Rossetti is more graceful – forming a kind of large wall mosaic through the juxtaposition of a myriad of squared stone tesserae arranged in a regular pattern, side by side, with each course staggered so that each stone lies at the mid-point of the ones immediately above and below: the result is that the vertices of the pyramids are diagonally aligned, thus creating a dynamic chiaroscuro effect. 1

Other important buildings constructed during the period between the end of the 15th century and the beginning of the 16th century adopted diamond-pointed rusticated façades: the so-called Steripinto building in Sciacca, Ciambra /or Giudecca) House in Trapani, Palazzo Raimondi in Cremona, and Palazzo Sanuti (later Bevilacqua).

At the beginning of the 16th century, rusticated ashlar had already achieved a certain pre-eminence among Renaissance façades with its transformation into a genuine architectural style. It often took on a composed, orderly form within a classical design, as can be seen in the buildings by Raffaello, Peruzzi and Sangallo the Younger; however, just one generation later, it was utilised in a more decorative, illusive manner, establishing a true style known as rustication (as in the work of Giulio Romano in Mantua). During the centuries that followed – with just the occasional important exception (Longhena’s Palazo Pesaro and Palazzo Rezzonico in Venice, for example) – rusticated ashlar was used in a much less spectacular fashion.

In more modern times, rusticated ashlar designs have been employed in ordinary constructions, where plastered façades have been adorned with “false rustication”. This technique of imitating rustication emerged in the mid-16th century, and can be seen in the Gongaza family’s Renaissance Mantua (a town lacking in stone at that time), where Giulio Romano’s skill was called upon to employ the rusticated masonry effect for purely decorative, illusory purposes.

Davide Turrini

Notes

* The re-edited essay has been taken out from the volume by Alfonso Acocella, Stone architecture. Ancient and modern constructive skills, Milano, Skira-Lucense, 2006, pp. 624.

1 For further details of the Palazzo dei Diamanti in Ferrara, see: Bruno Zevi, Sapere vedere l’urbanistica. Ferrara di Biagio Rossetti (Turin: Einaudi, 1971) (first published 1960). For a detailed analysis of rusticated cladding, see Carla Di Francesco (ed.), Palazzo dei Diamanti. Contributi per il restauro (Ferrara: Spazio Libri, 1991); Chiara Bentivoglio, “Luci e ombre nel rivestimento esterno del Palazzo dei Diamanti”, Marmo n.10, 2000, pp. 8-15.