1 Giugno 2011

English

Rusticated masonry*

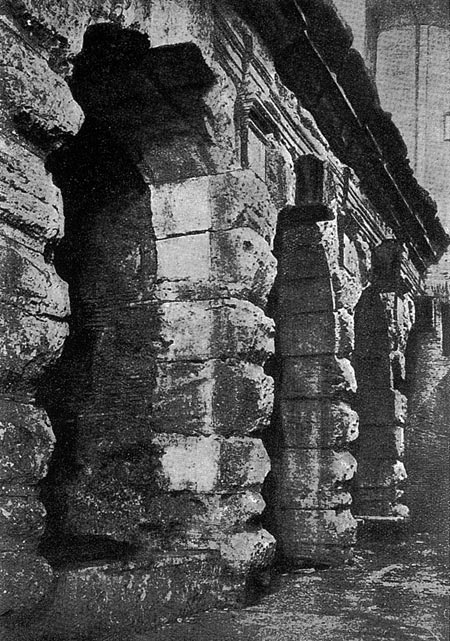

Selinus, city walls featuring rusticated ashlars (ph. Alfonso Acocella)

Up until now we have concentrated our analysis on various conceptions of masonry, and on its technical and architectural evolution from the original constructive methods. At this point we would like to go back to this theme and look at it from a different angle: that is, we wish to remain at the “surface” level and view a unique category of rather special walls.

As we have repeatedly pointed out, the figurative aspect of the opus quadratum depends, as with other types of stone wall, on a series of factors; these include the particular characteristics of the stone used, the size of the blocks, the system of bonding and the architectural design (in both superficial and spatial terms) of the walls in question, and, last but not least, the superficial treatment (dressing) of the facing of the masonry wall.

At this point, we are going to take a closer look at this latter aspect as it appears in rusticated masonry, beginning from its earliest Greek-Hellenistic forms and following its development in Roman architecture, which was to classify it as a true style of masonry.

As we have mentioned before, Mediterranean architecture has been characterised from its very origins by the use of dressed stone blocks – opus quadratum: the accurately cut, dressed and squared nature of these ashlars served to “connect” and “bind” during the construction of large-scale walls.

The facing of these blocks then often became the focus of attention of teams of masons, who set to work sculpting, shaping and “decorating” the ashlars: whereas in some case the facing of these stone walls was left perfectly smooth, as in the splendid masterpieces of the Athens Acropolis, in other cases it was given a more plastic, perhaps even “expressionist” finish which was to constitute the origins of all subsequent rusticated masonry.

The term “rusticated masonry” commonly refers to the arrangement of stone blocks (ashlars) with rough external faces that were only dressed along their joints, so as to emphasise the rough faces projecting beyond them, and thus the irregular facing of the wall as a whole.

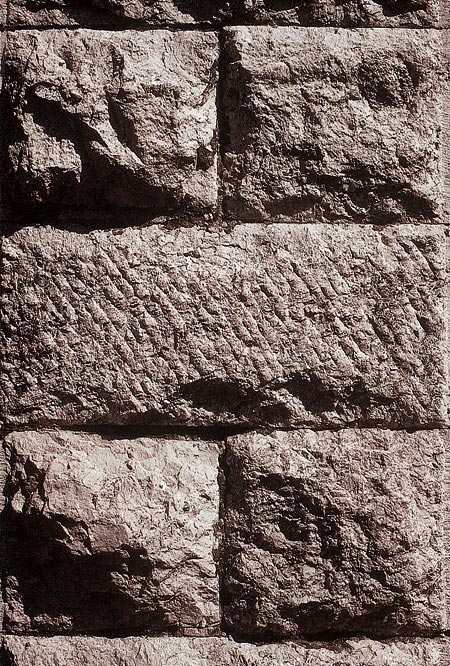

Rome, Temple of Divus Claudius. Arches featuring rusticated ashlars (ph. Alfonso Acocella)

This definition, which would appear to be excessively reductive, only identifies rustication with the manner in which all or some of the stones are left in their rough, original state: we would prefer, on the other hand, to consider rustication as covering all those methods of treating the faces of the stone designed to emphasise the facing of the wall as a whole (including those that leave the stone with an almost “flat” finish, in the Greek classical style), whereby the joints are in someway dressed to provide some degree of plastic character to the construction, with the face of each ashlar rendered distinct from the others as a result of this decorative dressing. In his treatise on “The Forms of Material”, Henri Focillon offers the following thoughts on the issue of rustication:

As soon as we consider the question of the evolution of the forms of material, we no longer separate the one idea from the other, and although we use two different terms, the aim is not that of rendering an abstract process objective, but rather that of showing the constant, indissoluble character of a real agreement. Thus form does not act as a superior principle that models a passive mass, since it could be said that the material imposes its own form in this forming process.

Similarly, it is not a question of material and form as such, but of materials in the plural – numerous, complex, changing materials with their own appearance, weight – the products of nature but not natural as such.

Several principles may be deduced from the above, the first of which is that each material has a certain destiny, that is, a certain natural vocation. It has a given consistency, colour and grain.

These are forms in themselves, and as such they call for, limit or encourage the evolution of artistic forms. They are choices, not only in terms of the ease of working, or of the degree to which art serves vital needs, but also because they lend themselves to a particular kind of treatment and produce certain effects. Thus their raw form stimulates, suggests, propagates other forms (…).

However, it should be pointed out that the natural vocation is not a blindly deterministic thing, since – and here lies the second point – these fascinating, highly characteristic and demanding materials, with respect to the forms of art upon which they exercise a kind of fatal attraction, find themselves radically modified by the latter.

Thus it is that a divide is created between artistic materials and natural materials, albeit united by their acknowledged mutual convenience. A new order is established. They represent two separate kingdoms, even if the craftsman and the workshop play no part. The wood of a statue is not the wood of a tree; sculpted marble is no longer quarry marble; melted gold is a new metal; a fired brick laid in a wall has little in common with the quarried clay it was made from. The colours, the texture and all the other tactile aspects of the material have changed. Those objects with no surface, hidden below the skin, buried inside the mountain or encased inside the nugget, have been separated from this chaotic state of affairs, they have acquired an epidermis, become part of space and been subject to the light that alters their essence.

Even if the treatment received has not modified the natural balance between the parties, the life of the material has visibly changed. 1

This passage would seem to encapsulate the subtle relationship between form and material that lies at the centre of Man’s every creative activity; in particular, Focillon’s analysis provides us with a new vision of rusticated masonry. Certain scholars have viewed this subject as the simple (almost natural) result of the need to economise on the stone required in the process of transmigration from the quarry to the workshop: however, while this need may well have been at the root of the subsequent development of rusticated masonry, it almost certainly gave way to the more deliberate pursuit of an aesthetic achievement, given the extremely wide variety of styles of rusticated masonry that have characterised stone architecture throughout history.

The choice of material, and of its “vocation” for rustication, has involved the rejection of certain types of stone in favour of others. At times, the choice has been determined by the strength and plasticity of the raw, rough material as found in nature, while at others it has been guided by the elegance and softness of the surfaces as modelled by the mason’s chisel. Rather than the colour or the smoothness of the stone’s surfaces, rusticated masonry focuses on the stone’s more “tactile” qualities – the depth and “plasticity” of the its wrinkled, corrugated surfaces.

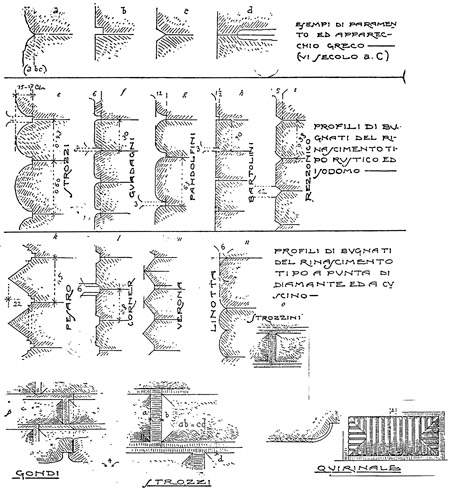

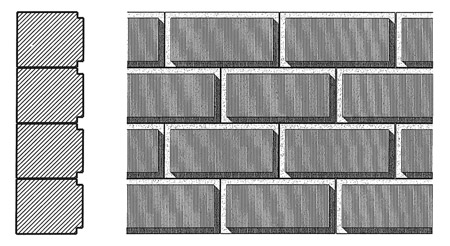

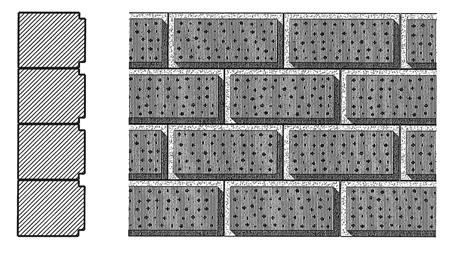

Illustrations of rusticated ashlar work taken from the volume ”L’ossatura murale” by G. B. Milani

Thus it is that, no longer satisfied with the strictly stereometric opus quadratum, with its smooth surfaces and pure, simple geometrical patterns, stone architecture witnessed the emergence of a style of masonry that to some degree managed to preserve the raw power of stone in its transformation from quarried material to artistic element.

The various varieties of rusticated masonry (quarry-faced, isodomic, “cushion-like”, diamond-pointed), through their “sculpted forms” and the ensuing contrast of light and shadow (rather than any change in colour of the stone), highlight the individual ashlars and the courses that constitute the masonry wall. Sometimes the stone left bearing its original, rustic, “brutal” traits gives the walled construction the appearance of natural rock; however, this likeness is only an apparent one, as Focillon tells us, because the craftsman has intervened, and the rock has been hewn, cut and dressed, and thus can no longer be considered a natural product in the strict sense of the word; the life, the essence of the material has been transformed by Man’s action.

In general, rusticated masonry is associated with the “poorer” (but without a doubt the most commonly used) materials, that is, stones as such; travertine is also used, and on rare occasions, marble or granite as well (in those areas where large supplies are readily available). The various forms of rustication constitute the valorisation of the broad family of opaque stones (those that cannot be polished), often found locally, re-arranged in masonry courses boasting a certain plastic quality. Rustication may thus be said to be a three-dimensional architectural method whereby the wall is perceived as a mass to be “sculpted” and “engraved” in depth. This involves a kind of architectural translation of the work of the sculptor, here required to create projecting rusticated features of various kinds.

The varied forms of rustication mentioned above each represent a form of “virtuoso writing” indelibly engraved into the stone body of western architecture. Light and shadow constitute the missing ingredients in the emergence of this now resplendent material.

Types of rustication

Rustication is called “cyclopean” when the external faces of the ashlars are left in their natural state, or dressed so as to appear as if they recently been taken from the quarry. The joints between the ashlars are deliberately “gouged” out to create a contrasting channel and to highlight the chiaroscuro effects produced by the dressed stone facing. This particular type of rustication is designed to emphasise the original, primitive character of the stone, and it utilises the material in such a way as to reveal its initial “brutality”, that is, the strength and imposing quality of the architectural construct. At times, the courses of rusticated masonry run parallel to each other, the ashlars aligned in a regular, linear pattern; at others, the ashlars in one course may be of a different height from those in the adjacent course, thus varying the sub-division and rhythm of the masonry facing. Alternatively, an opus quadratum approach may be adopted, whereby variously sized and

shaped ashlars may be used (ranging from the thin, long rectangle to the perfect square), thus interrupting the continuity of the masonry courses.

In diamond-pointed rustication, the ashlars are cut with chamfered, pyramid-shaped faces with a square or rectangular base. The overall design of the wall may be emphasised to varying degrees by means of the channelling along the edges of the pyramidal ashlars.

Rusticated masonry wall (ph. Alfonso Acocella)

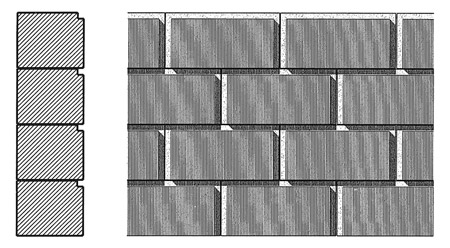

Isodomic rustication features ashlars with accurately dressed faces which are generally coplanar. These faces may be dressed using a variety of different metal percussive tools (facing hammers, tooth chisels, masonry chisels, etc.), or “combined” tools when dressing the edges of the ashlars to create a strip or band a couple of centimetres wide.

A second process involves the dressing of the edges to create a small channel which may run along the horizontal perimeter of the ashlars only (thus marking the height of the courses), or may run the entire perimeter of the stones (thus emphasising the character of the individual stones).

In isodomic rustication, the ashlar courses may not always be of the same height: indeed, they may be of varying height, or the ashlars themselves may be of differing dimensions, thus giving rise to a more complex facing design.

Further variations on this theme may be achieved by alternating “smooth” ashlars with truly rusticated ashlars, thus creating a pattern characterised by clearly-defined bands. The dressing of the facing depends on the required effect pursued each time.

Types off lat-faced isodomic rustication

[photogallery]bugnato_album[/photogallery]

Chamfered (or “cushion”) rustication is very common, and may be considered a variation of isodomic rustication, where the faces of the diverse ashlars are generally cut so as to protrude, forming convex or flat shapes with chamfered edges.

The convex forms may possess a smooth or a “frosted” surface (the latter has a series of vertical channels running across it).

Note

* The re-edited essay has been taken out from the volume by Alfonso Acocella, Stone architecture. Ancient and modern constructive skills, Milano, Skira-Lucense, 2006, pp. 624.

1 Henri Focillon, “Forms in the Realm of Matter”, in The Life of Forms in Art (New York: Zone Books, 1992) (originaltitle Vie des formes, 1943), pp. 96-98.