3 Settembre 2007

English

SOFT-STONE

Stone origami

“Poets translate into images the enchantment of the material…”

(Gaston Bachelard, Causeries, Aldephi, Milano, 2007, p.10)

The master Kengo Kuma’s (www.kkaa.co.jp) interest in stone, in its being a pure and variegated material, develops within a thematic unity in which we can identify the hidden genealogy, the origins, starting with the Stone Museum and continuing with the Louis Vuitton building in Osaka, the Tokyo Agriculture Museum, the Nagasaki Art Museum, Lotus House and the more recent Ciokkura Park shopping centre and Padiglione of Verona for Il Casone in Marmomacc 2007.

Assuming as a key to interpretation the characteristics with which Kuma on each occasion tackles the theme of stone – massiveness, lightness, fineness, slenderness, suspension, incision, deformation and erosion – it is possible to trace a thematic continuity between figurative solutions that are different yet “correlated” in the principle which dictated their genesis. Stone and its versatility: this is the theme tackled by Kuma. The exercise has been carried out on an apparently paradoxical ridge of interpretation: the immateriality of architecture. A “constructed immateriality”, acting on the rapports between material and light, on tactile sensations, on meanings related to the “construction of forms”.

Kuma cuts, folds, connects, overlaps, weaves, repeats to infinity a connective principle, which addresses, narrates. The subtle oscillations between abstraction and the sensitive manifestation of the material link back to a “sensitive approach” to architecture, a principle which Kuma revives from Japanese art and tradition.

Stone Museum, Nasu, Tochigi (1996-2000). Outside views Photo by Peppe Maisto

[photogallery]kuma_alini_album1[/photogallery]

In the Stone Museum the Ashino stone – volcanic stone – used to build both heavy-light and continuous-discontinuous structures, gives shape to a broad repertoire of architectural figures: screens, grilles, walkways, brise-soleils, paved surfaces, and cladding, to which correspond a similar number of stone finishes: smooth, bushhammered, honed, treated with acid, flamed, etc. The traditional solid and continuous masonry is articulated through the design of the material, thinned; the walls lose that sense of heaviness typical of traditional buildings. Although Kuma uses the stone in heavy layers, he makes its perception ambiguous by dematerialising it, he de-solidifies the material, creating porous “stone enclosures”. A “vibrant material”, obtained by staggering the joints, setting back the blocks, and interrupting continuity with 6-mm-thick Carrara marble slabs which let the light shine through, becoming evanescent.

Food and Agriculture Museum, Setagayaku, Tokyo, 2004. Interior. Stone brise-soleil system by Shirakawa. Detail of stone screen. Credit Archivio Kuma

The idea of a “porous wall” is a concept which “returns” in the Food and Agriculture Museum, a functional space used for teaching and research at the Faculty of Agriculture in Tokyo.

The museum’s stone shell is marked by the rhythm of Shirakawa’s stone brise-soleils, a type of stone which, owing to its porosity, changes colour over time. This metamorphosis caused by the ageing process of the material becomes an integral part of its figuration.

Nagasaki Art Museum, Nagasaki, 2005. Credit Archivio Kuma

[photogallery]kuma_alini_album2[/photogallery]

A theme which in the Nagasaki Art Museum also assumes symbolic importance. The material becomes an element of union between “that made by man and that made by nature”1, a “bridge” between landscape and architecture. Any opposition between natural and artificial materials appears to be cancelled out by a sort of “naturalisation of the artificial”.

Louis Vuitton, Osaka, 2005. Credit Archivio Kuma

[photogallery]kuma_alini_album3[/photogallery]

In the Louis Vuitton offices of Osaka, the stone loses mass, thinning to become a sensual polychrome surface. A slab of alabaster (4 mm thick) placed between two sheets of glass, reacts to the light, revealing what is concealed, enhancing the splendid pattern of the material with its

infinite wefts of colour. Kuma, once again, offers us a paradox: to make the invisible visible, dissolve the material in the light.

Lotus House, 2006 Credit Archivio Kuma

[photogallery]kuma_alini_album4[/photogallery]

Porosity, weft and suspension are concepts which govern the Lotus House project. Here, 3cm-thick travertine slabs, hooked onto a slender steel structure, define a discontinuous and regular surface. The stone, removed from the force of gravity, appears to “levitate” in the air, the solids dialoguing with the light and voids with the unfathomable depths of space as far as the eye can see.

Ciokkura Park, Tochigi, 2006 Credit Archivio Kuma

Ohya stone, that used by Wright for the Imperial Hotel in the Ciokkura Park shopping centre in Tochigi, on the other hand, “folds” to form a grid which Kuma defines as soft stone.

Kuma reinterprets an ancient building technique used in the construction of barns: a compact stone weft, yet full of “gashes”, incisions made inside the masonry.

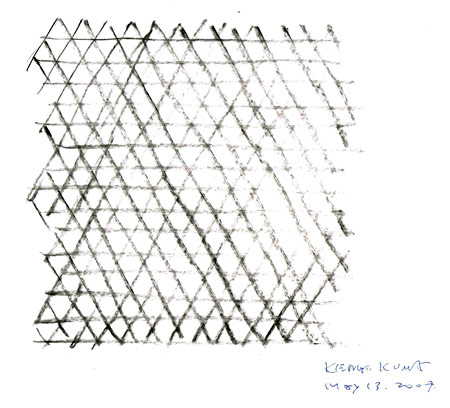

Project drawing. Padiglione for “Il Casone”, Marmomacc 2007, Verona (under construction) Credit Archivio Kuma

The Verona Padiglione in Marmomacc 2007

Folding is the generative principle governing the project for the Il Casone Padiglione, a project in which architecture is understood as a sensorial artificial work, an emotional experience in contact with the material. The “evocative power” of Kuma’s stone figures and their genetic imprint acts within us like the memory of inherited associations, a chain of links for new meanings. Kuma’s sensitivity to contemporary language crosses tradition with new eyes, reinterpreting it by renewing it. It escapes that “latent petrification” of which Italo Calvino had warned us (Alfonso Acocella, Sulle ali di Perseo).

Thus Kuma appears to us as Perseus, the redeeming hero, who escapes the terrible petrification inflicted by Medusa on her enemies thanks to a stratagem. An ingenious intelligence (mêtis) comes to his aid. That of Perseus is a multiple, multiform intelligence, backed up by technical know-how (tèkhne). Kuma, like Perseus, appears to cross reality through “double vision”, a double perspective: he looks to tradition with a “penetrating gaze”, he pushes his observation beyond the image, to the point of identifying a broader virtuality in the material, in its infinite wefts.

The pavilion designed2 for Il Casone of Firenzuola, a kind of origami3 of paper transformed into stone, proposes a personal interpretation of the lightness suspended between tradition and innovation. 1cm-thick slabs of pietra forte colombino4 are linked to form a “methodical module”, a kind of “perforated wall” where the material appears to distribute itself and spread out around the voids.

Kuma thins, intersects and spatially directs the stone, generating a self-balancing grid-like system: the weft, the interlacement and textures tell the architectural tale, which oscillates between density and void. The void and the material represent the project’s discontinuity: generating elements of the composition, devices through which Kuma unfurls his narration.

The pavilion, a kind of labyrinth of memory, is formed by a continuous wall which, as it unwinds, assumes multiple configurations and meanings.

The generating element – the basic module – is a tetrahedron obtained by assembling three 25x25x1-cm slabs. The stone slabs are bound using epoxy glue, a solution which guarantees both adhesion amongst the elements, according to the load sustained by the standard modules, as well as structural performance. The system is reinforced on one hand by the transversal horizontal elements, and on the other, by its own weight, which helps to stabilise and prevent overturning.

The stone modules weigh some 5 kg (the average mass of a volume unit is 2500 kg/m3) and have sharp corners. A choice which aims to enhance on one hand the geometry of the elements and on the other, their projected shadows.

The surfaces of the slabs are finished by hand. This treatment of the stone’s surface “feels the effects” of this hand action, which in some way is imprinted in the material. The modules expose the natural qualities of the stone, its geological formation and its “impurities”.

The conformation and geometric orientation of the elements create a grid-like composition, where void dominates mass. This perception is, nevertheless, counterbalanced by the effects of the light, by a refined technical device aimed at achieving a more complex figurative result5.

The light crosses the wall’s cavities in an upward direction, creating long shadows, softening empty spaces and modifying the relationships between mass and void. The triangular texture aims to create a vibrant surface, enriched with an infinite range of hues produced by the shadows.

This figurative device is enhanced by the geometry of the stone weft, which at the base reduces the section of “ground contact”. At the base, the modules are more slender, losing mass where instead, structural performance would require broadening. Once again, Kuma appears to want to place us before a paradox, contradict a “static necessity” to heighten the provocation of the design. The “barricade” of lights at the base makes the wall appear to float, giving the effect of being suspended and fluctuating in the void. A sense of labyrinthine, suspended lightness envelops the space.

Above, the diaphragm-wall is sealed by a continuous stone plane, which perfectly concludes the building’s upper part. From a structural point of view, the whole acts like a spatial reticular beam whose stability has required particular attention in terms of the system’s continuity, also during assembly of the elements. Specific needs have required the development of assembly procedures determined partly by the decision to make connections reversible, and partly by the need to facilitate the shifting of stone elements. In order to avoid using machinery and mechanical means to move and position elements, the decision was made to aggregate a number of modules to form macro-modules.

4,200 stone elements form a porous wall.

The final hypothesis for the design proposes a stone diaphragm, where the idea of solidity and compactness typical of a wall, is contrasted by that of lightness, transience and transparency. Concepts which cohabit inside a delicate dichotomous equilibrium. The wall, of varying height, unfurls around and inside the exhibition space, permitting, through its “folds”, a variety of activities and meanings: separating filter, exhibition space, warehouse, garden. The functions are arranged according to the different “specialisations”: table, shelf, desk, bookcase, display stand, etc.

The Pavilion space is organised around a kind of large square, from which the exhibition-communicative itinerary unwinds. The space is visually subdivided into two large areas by a partition, which also forms the physical limit between the exhibition and service areas.

A traditional garden of stones “surrounds the entire pavilion, which appears to have been placed upon a layer of pebbles. The sense of softness is enhanced by the rapport between analogous materials, which express a different visual morphology, a different way of “fragmenting”, reducing, segmenting.

Kuma seems to want to “force” the stone, using it in an unusual, informal, provocative, ambivalent, ambiguous way. Moreover, ambiguous derives from the verb ambiegere “to wander”, and is formed by ambi – “around” and by agere “to do”, which together give the sense of having two or more possible meanings, of “shifting from one side to the other” and of “having a doubtful nature”6. Kuma fulfils this shift by exploiting the expressive potential of the material. As is in the nature of his creative thoughts, he puts into relation apparently opposing concepts and meanings with a view to generating in the user a kind of “wrongfooting”, in other words, aporia. He brings us closer to other figurative worlds of the material, unveiling its latent potential.

The choice of a material monographism refers to an absolute concept. Kuma incites us to go “beyond” representation, to move through the territory of the “imagination as a repertoire of potential, in order to show us what it has not been, what it is unlikely to be, but what it could have been”7. In his actions, reflection and depth cohabit in an image of explosive power, a force which transcends its specific meaning and which, paraphrasing Warburg, we could define an image with memory of the future.

Through this ambiguous interpretation of stone, Kuma goes back to the original meanings which come within the construction of form, recovering a heritage of images that dwell latent within us.

Compositional unity is achieved through the infinite repetition of a surface-element. Between the part and everything, there is a bond of necessity and reciprocity. The images flow from one into the other, new nuclei of meaning emerge from the depths of time through the material, through the way in which Kuma shapes it.

In the project for the Verona Padiglione, the grid of the composition, the voids, the weft of the material and its infinite segmentations suggest an “intrinsic sacredness in the material”, analogous to that which governed the ancient art of the ceremonial folding of paper, noshi8. The wall, which can be perceived as a “mirroring” of a slender paper diaphragm, is the architectural figure through which Kuma proposes his interpretation of lithic lightness: a challenge against mass, gravity, heaviness. Kuma “transfigures the stone”, exploring its latent potential. He acts inside the “genetic code” of the material. The material is the generating element of compositional strategies, the principle through which Kuma introduces us to the existence of structures of unexplored, inexhaustible meaning: inherited memory, mnemonic energy.

The Padiglione assumes special meaning, also in view of the fresh collaboration among the world of project culture, that of production and that of research and university training. Links between technology and formulation, integration among various professional figures, the contribution of production organisations in the formulation of innovative building solutions, are just several aspects which have urged the team coordinated by Kuma to verify the possibility of experimenting a new project procedure. Aspects which have encouraged Alfonso Acocella and the author of this text (teachers, respectively at the Faculties of Architecture in Ferrara and Siracusa) to collaborate in this experience, achieved through the convergence of knowledge, within the project and its production, and subsequently transferred as “live knowledge” in the sphere of training. Extending university teaching to research conducted in production procedures represents the desire to steer universities towards new fields of acquiring data. And it is also to attempt to give a response to this need that we have chosen to promote a broad debate around this experience, using the blog as an area of discussion, verification, contamination and participation.

Luigi Alini

Go to Kengo Kuma & Associates

Notes

1 Declaration made by Kengo Kuma during a recent interview.

2 The team, coordinated by Kengo Kuma, is composed by: Javier Villar Ruiz, Kengo Kuma & Associates; Alfonso Acocella, University of Ferrara; Luigi Alini, University of Catania; Roberto Bartolomei, Il Casone; Stella Targetti, Targetti Sankey S.p.a.

3 Art of folding paper (from the Japanese ori, to fold, and kami paper).

4 Calcareous sandstone extracted in Tuscany.

5 The solutions regarding lighting engineering were developed in collaboration with Targetti Sankey www.targetti.it.

6 Cf. Ezio Raimondi, La retorica d’oggi, Il Mulino, Bologna, 2005, p.64.

7 Italo Calvino, “Visibilità” in Lezioni Americane, Garzanti, Milano, 1988, p.91.

8 t began in the Muromachi era (1392-1573). Akira Yoshizawa, a creator of origami and writer of the subject, has inspired a modern revival of this practice, with increasingly intricate models and new techniques like wet-folding, the practice of wetting the paper while folding so that the finished product maintains its shape better, or soft-folding, whereby the paper is folded more decisively or softly to create special effects.