8 Ottobre 2012

English

Grafton Architects.

Architecture as new geography

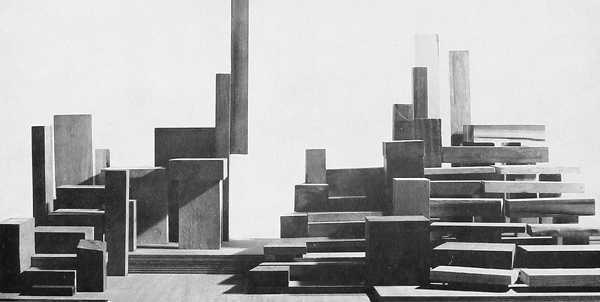

Grafton Architects, model of the enlarging of Bocconi University in Milan, 2008.

Focusing on the relationship between buildings and environment, human creation and landscape, that is to say between architecture and nature, is a necessary starting point in order to fully appreciate Grafton Architects’ work and in particular their pavilion at this edition of Marmomacc. These Irish architects themselves underline the recurrence in their work of the building thought as a portion of landscape, of the idea of architecture as new geography. Of the same opinion is Mendes Da Rocha, Brazilian architect they ideally connected with at the last Biennale: he once claimed that geography is the first form of architecture and landscape is the primeval construction.

These considerations can be helped by Bruno Zevi’s and Giovanni Michelucci’s critical approaches, attempting to create a link to history and nature, and to better understand our contemporaneity.

Interpretative model of the staircase in Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence (IUAV, 1964, professor Bruno Zevi, students Delponte, Farfoglia, Maddaloni, Monaco, Zagagnoni).

Nature

In 1964, celebrating the 400th anniversary of Michelangelo’s death, Bruno Zevi dedicated several essays to this artist in order to investigate the modernity of his works of art.

In those years at Venice IUAV, Zevi lectured about Michelangelo’s buildings: the result of this educational and research activity consisted in numerous models and creative photographical visions, mixing Expressionism, Surrealism and Informal Art; these works render a previously unseen problematic interpretation of Michelangelo’s architecture, emerging from an analytical critical approach that we can consider even today modern and daring.1

Among these works, an interpretative model of the stone staircase of Biblioteca Laurenziana in Florence stimulates a direct comparison with Grafton Architects’ pavilion, it being a composition of rectified blocks that distils the historical forms by Michelangelo keeping the timeless substance of a stone invading the space as a mountain, of a pile of monoliths becoming an upward structure, in both architectural and natural sense.

Grafton Architects, The Burren, Pibamarmi pavilion at 2012 Marmomacc, project render.

This concept is natural, and not naturalistic, because – as stated by Michelucci in a dialogue with Pietro Bellasi in 1984 – naturalism is “asking Nature some hints of architectural form”, and this is not the case.

In naturalism Michelucci saw a danger of turning Nature into a show, of overbalancing the human will imposed to the natural world or, vice versa, of men excessively exalting Nature and annihilating themselves into it.

“Nature, instead,” Michelucci stated, “isn’t a show, it hides in itself a mystery coming from its peculiar structure, and because of it the configuration of stones, layers and trees are constantly changing.” He also said: “I remember having seen, I don’t know in which Michelangelo’s work, a little detail in the space of the windows, a little seashell, a chiaroscuro element, a mass – well, in that simple chiaroscuro I saw the entire nature, the entire sea, the entire universe.”2

Michelangelo Buonarroti and Bartolomeo Ammannati, staircase in Biblioteca Laurenziana, Florence, 1534-59.

We can conclude that, in that detail, there was the mystery of the balanced connection between men and Nature in the sign of the architectural creation: it’s this point we must concentrate on, in particular on the possibility of fixing that mystery in the architectural act, of choosing and stylizing natural elements and textures into human construction, as happened in the Laurentian staircase or in several Michelucci’s works – as the church of San Giovanni Battista on the motorway, with its branch-like pillars – or happening today in the rocky and compact, yet welcoming, works by Grafton Architects. These Irish Architects express in fact the capacity of building a natural form of architecture, hard as a geological conformation, giant but never superhuman, always commeasured to the human scale.

Grafton Architects, Economics Department in Dublin, 2007.

This is evident in the exhibit staircase shown today, called the Burren to recall the stone pavement of the Irish Clare, in the cave-like plasticity of Bocconi University, or in the eroded monoliths of the educational buildings in Limerick and Dublin, or even in the vertical development, similar to a cliff, of the Lima university campus.3

In this way, the natural – not naturalistic – architecture by Grafton studio registers the topography, searches for suggestion in it, develops its characteristics in a demiurgic act, modelling a “new geography”; it seems very close to us because of its nudity, its telluric force, its reconnection to a fertile original dimension.

Grafton Architects, The Burren, Pibamarmi pavilion at the 2012 edition of Marmomacc.

The nature of the Burren

“A week of sweeping fogs has passed over and given me a strange sense of exile and desolation. I walk round the island nearly every day, yet I can see nothing anywhere but a mass of wet rock, a strip of surf, and then a tumult of waves.

The salty limestone has grown black with the water that is dripping on it, and wherever I turn there is the same grey obsession twining and wreathing itself among the narrow fields, and the same wail from the wind that shrieks and whistles in the loose rubble of the walls. (…)

It has cleared, and the sun is shining with a luminous warmth that makes the whole island glisten with the splendour of a gem, and fills the sea and sky with a radiance of blue light.

I have come out to lie on the rocks where I have the black edge of the north island in front of me, Galway Bay, too blue almost to look at, on my right, the Atlantic on my left, a perpendicular cliff under my ankles, and over me innumerable gulls that chase each other in a white cirrus of wings.”4.

The changeable and unpredictable strength of the Burren, of the rocky landscape of the Irish Clare, is clearly depicted in John Millington Synges’s journal about the Aran Islands. Near them, bounded by the cliffs of Moher and Galway Bay, we can find the Burren, a vast limestone karst pavement emerging from the Ocean, petrified and criss-crossed by cracks.

A view of the Burren, limestone pavement in the Irish Clare.

Apparently bare and desert, the Burren is actually very favourable to the living world that grows there every season thanks to little ponds created by the rain and protected by the rocks. As mentioned before, Grafton Architects used this evocative environmental metaphor for the Pibamarmi pavilion at 2012 Marmomacc.

From natural landscape to exhibition design setting, The Burren becomes in this way a synonym of the stone presenting itself to the visitors naked and primeval, in the stylized form of a three-dimensional floor, of an exhibition cliff that extends vertically giving space to its unexpected, cave-like interior rooms.

Grafton Architects, The Burren, Pibamarmi pavilion at the 2012 edition of Marmomacc.

This time, the new geography conceived by Grafton Architects, this portion of landscape modelled within a context completely created by men, takes inspiration from the harsh forms of the Nordic landscape, from the salty black rocks of the Aran Islands in the Atlantic, tangible and close but always intact in their loneliness; Grafton Architects distil the dark curves covered by mists and haloes of these enigmatic places, giving back to the visitors a composition of different shades of leaden greys, of monoliths including little water pools and white design elements in marble enchased in its gaps.

Go to:

Grafton Architects

Pibamarmi

Notes

1 Zevi and his IUAV students’ interpretations about Michelangelo’s architecture are documented in Bruno Zevi, Michelangiolo architetto, Milano, ETAS, 1964, pp. 66, (re-iusse of L’architettura. Cronache e storia, n. 99, 1964);

2 Giovanni Michelucci, “La città degli uomini. Colloquio con Pietro Bellasi”, Studi cattolici, n. 43, 1964, p. 18;

3 Abou Grafton Architects see also Ettore Vadini (edited by), 4×4. Sedici opere di architettura contemporanea, Pescara, Sala, 2011, pp. 54-77; for the Bocconi’s building in Milano see also Francesco Cellini, “Sull’ampliamento dell’Università Bocconi”, pp. 76-79, in Vincenzo Pavan (edited by), Litico etico estetico, Milano, Motta, 2009, pp. 157;

4 John Millington Synge, Le isole Aran, Palermo, Sellerio, 1980, (tit. or. The Aran Islands, I ed. 1907), pp. 43-45.