8 Marzo 2011

English

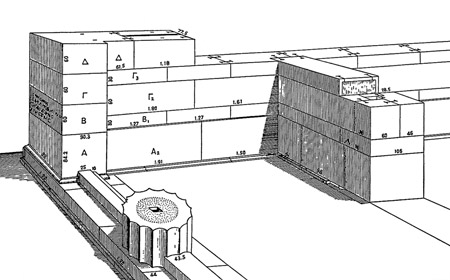

Opus quadratum*

Entrance to the tholos – the Treasury of Atreus – at Mycenae (ph. Alfonso Acocella)

The corridor walls at the entrance (dromos) to the Treasury of Atreus at Mycenae already provide a mature example of opus quadratum, albeit one composed of different-sized stone blocks arranged in horizontal courses of differing height. The transition from Mycenaean to Greek civilisation (between the 13th and the 8th centuries B.C.), characterised by Hellenic architecture’s adoption of stone as its principal building material, continues to constitute a rather dark historical period about which relatively little is known; indeed, we are still awaiting those archaeological finds capable of revealing some of the “secrets” of that transitional age.

Nevertheless, one trend in Greek architecture during the early Archaic period is clear: the 8th and 7th centuries B.C. saw a gradual, conscientious (and eventually successful) effort being made to master the hard-wearing, “noble” stones (poros and limestone initially, followed by marble), together with the artistic definition of the architectural order, and the perfection and refinement of opus quadrata.

Mainland and Ionian Greece’s debt to the eastern Mediterranean civilisations (i.e. to Minoan-Mycenaean culture on the one hand, and to Phoenician, Syrian and Egyptian culture on the other) is a widely acknowledged fact now; however, this does not diminish in any way the creative spirit of the ancient Greeks themselves, who in their experiments within a series of small city-states (poleis) successfully developed the utilisation of stone in what was to become a technically and artistically perfect form of architecture.

Throughout the early Archaic period (albeit within the context of the political independence of each single poleis), there was a growing awareness of a common koine, an expression of a commonly-shared culture and religion. Sacred sites such as Delos, Delphi and Olympia were soon to become important Panhellenic sanctuaries (and to a certain degree “political centres”). In these sacred areas, which were also to become “showcases” for Greece’s artistic spirit and technical ambitions, supported by promoters funding the construction of treasuries, sacred buildings and so forth, the two great architectural orders and the stone-built peripteral temple were to emerge, together with an incredible passion for the perfection of the masonry wall. All of this was the fruit of artistic experimentation, and in particular of the work of Greek sculptors and stone masons. In the words of Roland Martin:

In the technical field, craftsmen began to try and master the noble materials such as marble and limestone; thus it became possible to extend and to increase the number of floors and the size of rooms so as to adapt them better to the purposes of the building. During the course of the 7th century B.C., the main achievement consisted in the introduction of hewn stone onto building sites, which gradually replaced the “poorer” materials such as wood, brick and earth, mixtures of clay, stones and straw, and crushed stone. The lessons learnt from the sculptors further nourished the effects of the discovery of the architecture of neighbouring countries such as Syria-Phoenicia and Egypt. The stone masons worked closely with the sculptors, and in fact the considerable ability of the former was a fundamental prerequisite of all the great works of Greek architecture. The previously employed wooden pillars were replaced by slender stone columns; the wooden planks used to clad the corners and the extremities of walls were replaced by stone antae and large blocks, while the rough stone basements of the brick walls gave way to large orthostats surmounted by blocks of soft poros, cut into brick-like shapes (and called by the same name); finally, the wooden and terracotta parts of the roof were easily replaced by stone elements. Thus it was that the end of the 7th century B.C. saw the advent of a technique that freed the creative spirit and enabled architects to go beyond the mere groping in the dark and the rather ephemeral achievements of the mid-8th century B.C. witnessed in various parts of the Greek world, and in particular on Crete and in the Cyclades. 1

Promontory of Sunium, the Temple of Poseidon. The pseudo-isodomic wall

For a lot of people, Greek architecture is synonymous with sublime works in natural stone and marble created between the Archaic and the Classical periods, portrayed in black and white in the volumes of art history we were given as school pupils, or more recently, in a wide range of works produced by international publishers now boasting colour photographs. However, this fascinating (and to a certain extent, stereotyped) vision only emerged after some three centuries of building history, during which the emphasis was decidedly on more practical, utilitarian and “rudimentary” aspects of architecture: the above-mentioned sublime works only emerged during the 7th and 6th centuries B.C., when Hellenic architecture reached its technical and aesthetic perfection thanks to the use of squared or shaped masonry which was subsequently sculpted and worked in situ.

The oldest Greek buildings – those erected between the 11th and the 8th centuries B.C. and of which we still have only very partial knowledge – were constructed in wood, in baked clay parallelepiped bricks, with foundations of stone aggregate or roughly squared stone blocks. Recent excavations have revealed that early Greek architecture was not based on the complex masonry techniques utilised in the Mycenaean palaces and cities.

The earliest archaeological finds on Greek soil reveal fragile, rudimentary remains associated with separately-built residential constructions. Those dwellings dating from the Geometrical period (11th – 8th centuries B.C.) consisted of just one room – initially elliptical, then apsidal or rectangular – created from baked-clay (or rammed-clay) bricks laid on stone foundations.

This form of construction was of crucial importance for the subsequent advent of squared ashlar masonry, as it remained a constant feature of the new models of stone architecture within the Greek world. In particular, there were those walls made of the two materials together: the base of the wall was in stone (and as such acted both as a foundation and a damp-proof course), while the rest was in baked-clay bricks surmounted by a wooden roof.

Within the framework of the conversion to masonry walls, which was first seen in the Greek’s monumental sacred constructions – this layered, hierarchical structure was transferred above all to the main nucleus of the religious organism represented by the cella designed to accommodate the statue of the chosen divinity. The regular stratification of the baked-clay bricks undoubtedly provided the model for the later “all stone” and “all marble” walls – thus transforming the original cobblestone and brick wall into a stereotomic work (consisting of regular, perfectly squared stone blocks) of a totally homogeneous kind in terms of the materials used throughout, from the foundations right up to the roof. It is interesting to note that the new stone blocks were to be called the same as the original baked-clay bricks were.

Athens, Propylaea. The isodomic masonry wall in blocks of Pentelic marble (ph. Alfonso Acocella)

Cut and dressed stone was also to play its part in the evolution of the slender wooden pilasters of early chapel porticoes and porches into robust, powerful columns.

In the chapter on columns and pilasters, there is a detailed account of the evolution of the character and role played by columns within the overall formalisation of the peripteral temple, which illustrates just how Greek stone architecture has seen the development of two interpretations of the use of stone: there is that of the specific use of the new material – of particular interest in this chapter – seen from the stereotomic point of view (whereby the wall is designed to establish the stratification of the material in two directions, spatial character and external volumetric emphasis) and in tectonic terms, perceivable in particular in the architectural evolution of the peripteral temple, with its colonnades opening out towards the external area where the use of stone “betrays” its derivation from wooden prototypes, in particular the “hut” with its traditional “colonisation” of the land in the form of separate structures dotted here and there.

The same peripteral temple in some way links up with our theme of the stereometry of walls: if we take the example of the mature stone temple, which finally emerged during the 7th century B.C. , we can see the central nucleus (the cella), through the “filter” of its outer colonnades, as a stone construct encompassing a closed space designed to protect and conserve the divine statue.

The walls of the classical Greek cella were made of poros, this rough, porous stone from the north-western region of the Peloponnese which had to be rendered, or of hard, compact limestone, or in the case of the more prized examples, of marble: the splendid “white” marble from the island of Paros; the marble from Mount Pentelikon, brilliant when cut and quarried but a few kilometres from Athens, which was used to build all of the most important constructions of the Periclean period: the Parthenon, the Propylaea, the Erechteum, the Temple of Zeus Olympus. On rare occasions, multicoloured marbles were also used (they were only extensively employed in the architectural field in later Roman times); one example of a limited use of coloured marble – the famous black marble of Eleusis – is documented in the Propylaea designed by the architect Mnesicles. The specific nature of marble – its compactness, its ease of working and sculpting, its shiny quality, its lightness of colour etc. – enabled the builders of Athens to achieve stereotomic walled structures characterised by amazingly precise joints, wonderfully smooth, shiny surfaces, often embellished by some of the most perfect and refined inserts and mouldings that architecture has ever produced.

Delphi. Wall with engravings and toothing stones visible on the facing of the ashlars (ph. Alfonso Acocella)

The opus quadratum, in its most elegant and characteristic forms, as represented by isodomon and pseudisodomic masonry, was to become the “stereotype” of Greek architecture, which was first to reach its perfection in the construction of sacred and monumental buildings (and only later in that of city walls and residential buildings). Indeed, its considerable success and influence in the field of sacred architecture throughout the archaic and classical periods was a vital factor in its later widespread employment in the construction of city walls, in the substruction of terracing and in civil construction, from the late classical period and subsequently throughout the Hellenistic period.

In the 5th century B.C., the perfectly proportioned and constructed opus quadratum reached a peak of popularity, and could be found throughout the entire Hellenic koine. Based on the use of carefully dressed parallelepiped blocks of suitable stone, compared to the more rudimentary methods of building stone walls, the opus quadratum made building itself that much simpler and safer – walls built in this manner being capable of supporting greater loads – and the end product was far more attractive – especially when marble was involved – than anything ever achieved before.

As well as the perfect way these stone blocks were cut throughout the 5th and 4th centuries B.C., the Greek opus quadratum was particularly characterised by the variety of surface finishes, of ways the outer faces of the blocks were “decorated”. While the least celebrated buildings featured blocks with their rough “quarry” faces in view, the more representative constructions consisted of blocks whose faces had been dressed to some degree – some were simply levelled, others dressed using special techniques to produce ashlar or rusticated masonry.

An attempt was also made to produce a chiaroscuro effect – especially in the case of the long, stark city walls of the classical and Hellenistic periods – by simply leaving the occasional block protruding from the rest, and by dressing the faces of the blocks to produce marked rustication. Other methods of embellishing such walls, discovered by archaeologists, include the chamfering of the ashlars to produce a softer, “cushion” effect.

Pompei. Wall of tufa stone with smoothed edges (ph. Alfonso Acocella)

The opus quadratum, however, was originally designed to highlight the perfection and regularity of the wall, and as such is often found in its simplest form, especially in Greek architecture’s most representative works, consisting of a perfectly level surface that extols the purity and clarity of architectural volumes.

In such cases, the design tends to be characterised by the completely homogeneous development of the wall, with just the merest hint at the individual nature of each ashlar (or row of ashlars) involving the “banding” of the facing perimeter. This type of finish – which may involve the central part of the ashlar being left in a “rusticated” state, or levelled and then carved – may characterise all four sides, or just two (the horizontal ones), of the external face of the ashlar: in the latter case, the horizontal development of the wall is emphasised, whereas in the former case, the additive logic of the construction is underlined.

A further way of characterising the opus quadratum is that of carving the facing, as often happens in the case of polygonal walls, with close-knit series of parallel, vertical grooves.

Note

* The re-edited essay has been taken out from the volume by Alfonso Acocella, Stone architecture. Ancient and modern constructive skills, Milano, Skira-Lucense, 2006, pp. 624.

1 “Architecture”, by Jean Charbonneaux, Roland Martin, François Villard, Archaic Greek Art 620-480 BC (London: Thames and Hudson, 1971), p. 3 (original title Grèce archaique, 1968).