18 Gennaio 2011

English

The construction of walls. Walls/Space*

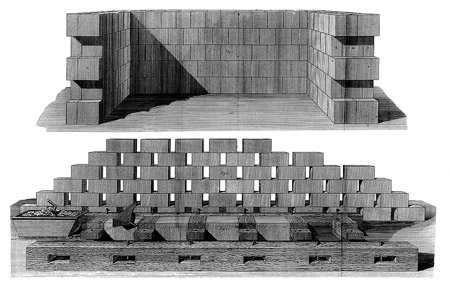

Plate of a square ashlar wall taken from the book “Trattato teorico pratico dell’arte di edificare” by Giovanni Rondelet

During a certain period in the very distant past (so distant as to make it difficult to define the exact temporal identity and geographical coordinates thereof), a stable form of long-lasting, protective architecture emerged from within a largely inhospitable natural environment, which in a certain way “perfected” that environment for “residential” purposes, based on the bodily needs and symbolic, intellectual aspirations of Man. The principal part in this silent revolution was played by the wall, designed to separate an interior space (a liveable microcosm) from the outside (the boundless natural world); in this process of “delimitating” and “structuring” the physical environment, the wall emerged as the boundary between the two separate worlds.

There is no point in underling the fact – as many scholars do – that nature already possessed its own geologically-formed concave and convex arrangements (hills and valleys, spurs and caves) capable of delineating diverse “spatial” possibilities other than the horizontal plane of the Earth’s surface. The particular nature of an architecturally-conceived interior space, separate from the atmospherically-conditioned external environment, presupposes the clear opposition of stereometric volume and emptiness very different from the type represented by the geological uplifting of the Earth’s surface, which merely creates the opposition of convex and concave.

The same can be said of the wall. Although the suggestive image of the “natural wall”, consisting of a rock face projecting from the ground, has always been present in the Earth’s landscape, the deliberate action of creating the archetypal manmade wall required a determined act of will, given the need to select and adapt the materials furnished by nature. Dom Hans van der Laan claims that:

The primary datum of the wall-separated space is the unlimited mass of the earth with the limitless space above it; so the limited mass of the walls must also be drawn from the earth in order to withdraw a limited piece of space from the space of nature. However, clearly the wall that encloses the space cannot be got from the earth-be it a block of stone, a piece of wood or a lump of clay-cannot produce the enclosed form of interior space directly; for this at least a few pieces of material need to be joined together. Dolmens and other megalithic monuments are examples of such primitive space-formation by means of a minimal number of pieces.

Euryalus Castle in Siracuse

Thus the wall first emerged as the “sum” or “aggregate” of naturally available materials. However, while tree trunks, branches, bushes and bulrushes constituted readily available materials for the construction of Man’s earliest rudimentary shelter – the hut – earth and stone were soon to be employed, with a little more technological input, to advance the concept of the wall as a vertical, solid, windproof, rainproof, soundproof structure capable of protecting those inside from the intrusion of wild animals and, indeed, of other people.

The materials used in building the latter variety of shelter were “gathered” from the Earth’s crust (or prised away from the various geological strata) to then be re-assembled into artificial units deemed “effective” in terms of their static characteristics.

Stones of all kinds, arranged side by side, one on top of the other, combined in a variety of manners, have always expressed the existence of a creative, ordered mind; like weaving, stone masonry involves the language of combination and composition. Depending on the stone available and the architectural purpose in question, the primitive world offers a variety of different constructional methods and approaches. Such methods bring to the fore the irregularity or the precision of the dressing of the stone and of the masons’ building expertise, and of the evolution of the technical aspects of building with stone.

The more primitive of walls include those built using “shapeless” stones gathered from the ground or “broken off” rock faces in local quarries. These stones may be rough, sharp-edged or worn by the elements: whether boulders, quarried rocks or pebbles from the riverbed, the size and shape of such stones is always going to be determined by natural factors, by the petrographical characteristics of the cleavage of the outer layers of the Earth’s crust.

Walls built using rough, “shapeless” material may have been what generated the taste for “rusticated ashlar”, where the dressing of the stone is governed by the attraction of stone’s natural value – stone perceived in its geologically-shaped form – almost as if the design of the wall is conditioned by a material resistant to the modelling force of the geometrical order.

The polygonal wall, on the other hand, was to represent a different architectural structure, with its dry-laid stones perfectly matching to form an essentially coplanar surface characterised by grid-like joints resembling the cracks in sun-baked clay.

Regularly-shaped stone walls clearly require blocks of stone with regular surfaces, according to a given design and cut: in order to obtain such material, the stone is taken directly from the earth’s crust in the form of massive blocks, and these are subsequently hewn into ashlars; the arrangement of the ashlars in superimposed courses of the wall could be seen as the re-composition of the natural strata of the sedimentary rock from which the stones were hewn.

The city walls at Alatri

The use of mortar, an innovation introduced during the Hellenistic period and characteristic of the area around the “Greek-Samnite” Bay of Naples, was to provide masonry will new technical potential and figurative options. Mortar, this supplementary building material, was to constitute the continuous, all-encompassing bed “imprisoning” even the most irregular of stones, and as such was to lead to the emergence, and subsequent success, of the Roman opus incertum. Thus the principle of gravity underlying the construction and strength of dry-stone walls, was now aided by the introduction of this bonding agent; the “discontinuous” presence of the stones in the dry wall was supplemented by the continuous design of the network of joints characterising the mortared wall. In this new conception of the stone wall – and in particular in the case of those walls with particularly wide gaps left between one stone and the next – the stone itself appears to constitute the background against which the network of joints stands out.

We shall be looking at the specific methods of stone wall construction a little later on: for the moment, we would like to remain a little longer on the subject of the spatial aspects of walls.

The action of “gathering” or “extracting” material from the natural environment for the purpose of creating a given architectural space, basically derives from Man’s need for “confined”, comfortable spaces that in themselves represent the essence of his own existence.

The space that nature offers us-claims Dom Hans van der Laan-rises above the ground and is oriented entirely towards the Earth’s surface. The contrast between the mass of the earth below and the space of the air above, which meet at the surface of the Earth, is the primary datum of this space. On account of their weight all material beings are drawn into this spatial order, and live as it were against the Earth. Through his intellect and his upright stance man can detach himself from this order and relate to himself the piece of space that he needs for action and movement. He is conscious of a horizontal orientation centred upon himself in the midst of the vertical orientation centred upon the Earth-of a space around him in the midst of the space above the earth.

Architecture is born of this original discrepancy between the two spaces-the horizontally oriented space of our experience and the vertically oriented space of nature; it begins when we add vertical walls to the horizontal surface of Earth. Through architecture a piece of natural space is as it were set on its side so as to correspond to our experience-space. In this new space we live not so much against the Earth as against the walls; our space lies not upon the Earth but between walls.

The search for a sufficiently large space (which subsequently gradually grew in size) designed to satisfy Man’s conception of life together with his aesthetic requirements, was to become a permanent feature of Man’s existence, one that has yet to exhaust its influence over the course of architectural history.

In rocky areas, natural caverns – shaped by the forces of nature during extremely remote times – already constituted an embryonic form of “proto-architectural” spatiality corresponding to those rocky masses eroded by nature or subtracted from the latter as a result of their transformation by Man’s endeavour. However, although such subterranean spaces are often of considerable size, they do not significantly modify the surrounding area: although they can be inhabited, they do not possess their own separate identity as spaces created by Man. True architectural spaces are not the result of the exploitation of gaps in the Earth’s crust, but of an intentional effort to create spaces, to carve them out of the infinite extension of the Earth’s surface, using walls as artificial boundaries designed to define the extension of large stereometrical volumes rising up from the ground.

In introducing the idea of authentic architectural space, we have referred to walls and then to the stereometrical volume created by those walls. We would like to specify that a single wall erected on the surface of the Earth, albeit constituting a meaningful separation of sorts, does not in fact affect the unlimited natural extension of the said surface. In other words, all it really does is sub-divide the natural open-air surface which, only partially delimited by the height of the wall, remains free and limitless in all other directions. Each of the natural environments on either side of the wall continues to conserve its original character; the geographical extension of the land has not been abolished but only interrupted. What we still do not have is the “formalisation” and “enucleation” of a true existential space.

In order to create a separate architectural space, distinct from the immeasurable extension of the Earth’s surface, we need to “bend” the wall or to erect a pair of parallel walls positioned in such a way as to produce a spatial “enclosure”, as was achieved in early times by the sacred Egyptian enclosures, or the walls of Mycenaean cities or of the temenos of the Greek sanctuaries, where a clear section in the Earth’s surface was “hemmed in” between enormous stone walls. This type of construction marked the advent of the true architectural space.

The city gate at Alatri

Archetypes/Recent developments. An analysis of the main differences, together with a closer look at those characteristics that distinguish the stereotomic construction from the tectonic one, underlie the organisation of the present chapter. The opening section has focused on a very important aspect of western civilisation – which clearly emerged in that very distant Mycenaean world – consisting of the stable, eternal presence of those walled structures that constituted the fortresses and tombs of the Mycenaean people, and that were to subsequently represent a radical and permanent transformation of the natural landscape.

A considerable part of the chapter on Stone Walls is taken up with a survey of archetypal walls: this digression is not meant to be a nostalgic tribute to the past or a “return” to our ancient origins, a world far removed from the uncertainty and difficulties of the present, but rather an attempt to return to the origins before investigating the more recent developments within this field.

Our examination of ancient walls attempts to preserve the necessary scientific and historical rigour, and awareness of the very latest archaeological discoveries – albeit within the logical confines of a larger work investigating a broad range of aspects of stone architecture both past and present: however, rather than a philological treatise, it is designed to be an interpretative, strongly “subjective” instrumental account of Man’s present-day cultural project. The focus on ancient origins particularly interests us for its underlying “working” hypothesis.

As the great architects of each age have always taught us, we would like to adopt a suitably critical, active stance with regard to the archetypal stone walls, perfected and codified over lengthy periods in history, rather than simply contemplating their nature in an erudite, yet uncritical fashion. Such an approach is designed to enable us to perceive their latent conceptual valence and contemporary worth. We believe the refinements expressed by the original creators of such archetypal stone constructions merit closer analysis and comparison with more modern architectural designs; if the latter are to be fully understood, then this search for the origins is of prime importance. To this end, the ancient world can be a concrete source of ideas and knowledge which may be employed in contemporary design, as Carlo Truppi seems to affirm when he states that:

Architecture perceived as a gradual activity leads to the belief that the substance of the subject remains unchanged, despite the continual modifications made. It makes sense, therefore, to search for the prototypes, the origins, the embryonic layers: in other words, to delineate the real depth of present-day architecture, its “archaeological” roots. Indeed, archaeology wishes to bring to light the regular development of building practices, the evolution of its contents, the ways in which ideas emerged, procedures were established, experiences were reflected in other experiences, trends emerged, ebbed and then re-emerged once more.

The Cemetery at Parabita, designed by Alessandro Anselmi e Paola Chiatante

We would like to underline the exuberance and wealth of Mediterranean stone architecture – inextricably connected as it is to Greek civilisation –in particular the degree of continuity between past and present. The archetypal walled construction is associated with the theme of the permanent architectural creation; it may never be cancelled from the history of human constructions, but only “renewed” through an incessant “re-writing” of the use of stone, of the compositional variation of volumetric bodies that fix spatial conceptions in time.

In general, the earliest stone walls, unlike their baked-clay counterparts or the Roman concretion variety, can be seen as a kind of mosaic characterised by all the various possible ways of combining stones to form a continuous vertical structure. At a certain point these early walls were to curve to form arches and vaults, and to continue along a horizontal plane to form floors and paving, using the same material; however, such developments go beyond the scope of the present chapter on Stone Walls, and as such will be dealt with separately later on in this work.

Note

* The re-edited essay has been taken out from the volume by Alfonso Acocella, Stone architecture. Ancient and modern constructive skills, Milano, Skira-Lucense, 2006, pp. 624.