7 Gennaio 2010

English

STONE, LIGHT AND TIME.

Alberto Campo Baeza and ‘La Idea Construida’

The antiquarium in the pavilion “La Idea Construida” at 2009 Marmomacc. In evidence, next to design pieces by Pibamarmi, the historical casts lent by Florence Accademia di Belle Arti. (ph Giovanni De Sandre)

In contrast to the pervasive spreading of prêt-a-porter architectural images, seductive but fugacious, and yet facing a project characterized by a transient nature, Alberto Campo Baeza once again gives us a deep reflection about the timeless values of thinking and realizing architecture.

Indeed, the rigorous proposal of the Spanish architecture for “La Idea Construida”, the pavilion created by Pibamarmi in occasion of 2009 Marmomacc, got corporeality starting from two themes inextricably linked to the archetypical themes of gravity, space and time, on which architecture has always grounded its bases: the valorisation of the relationship stone-light and the composition of an antiquarium with memories of the Ancient times.

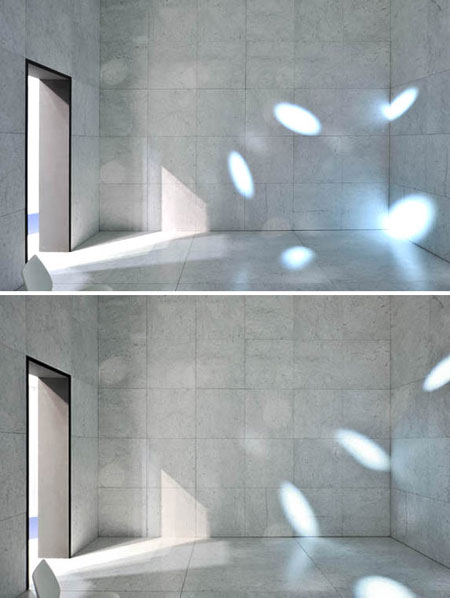

The pavilion offers itself to the visitors as an introverted space immersed in the penumbra, a void stone chamber destined to pause and meditation, ermined with Carrara marble and signed by the slow passage of luminous rays on the natural surface of the stone; exteriorly, instead, the setting presents design pieces by Pibamarmi ranged in a wall gallery, as finds of an antique collection together with historical casts of Classic and Hellenistic statues lent especially for the occasion by Florence Accademia delle Belle Arti.

The interior space, cubic and minimal, expresses a sum of long elaborations operated by Campo Baeza on the relationship among the gravity force of the stone, pure geometries, luminous static or dynamic energy, and the perception of time flowing; the antiquarium added a further degree of interpretation of the relationship between the work of men and the temporal dimension, in a mosaic of refined poetic shapes and proportions.

Detail of the antiquarium designed by Alberto Campo Baeza for Pibamarmi pavilion at 2009 Marmomacc. In evidence the cast of a relief from the Parthenon lent by Florence Accademia di Belle Arti.

Gravity and Space, Light and Time

“Gravity builds Space, Light builds Time, gives reason to Time. Here are the central topics of Architecture: the control of Gravity and the relationship with Light. The future of Architecture will depend on the new possible comprehension of these two phenomena”.1

Alberto Campo Baeza’s relay on the timeless value of Gravity and Light in architectural construction is strong and is stressed in his works as well as in the numerous theoretical contributions published since the end of the ‘70s till nowadays. Gravity force and luminous energy are considered decisive and fondant factors of architecture; these elements are transferred to contemporaneity thanks to the deep awareness of History, that, according to Baeza, is a vivid and inextricable presence to be valorised in a process of continuous deconstruction, analysis and re-interpretation of its archetypical elements and languages.

Among the various models which the architect recalls, the Pantheon in Rome is cited several times (also in the case of “La Idea Construida” pavilion) as an absolute reference, appreciated for the peculiarity of its oculus that allows the continuous passage of the solar luminous flow; a natural, changeable, dynamic light filters through the big opening constructing a huge sundial that makes the dimension of Space and the progression of Time comprehensible.

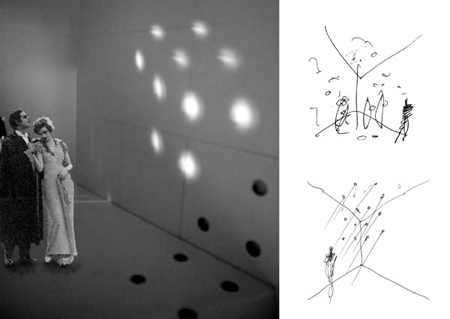

Alberto Campo Baeza’s sketches for the interior of “La Idea Construida” pavilion.

For Campo Baeza, then, the idea of Gravity is linked to the presence of Stone, and even when he doesn’t employ stone materials his architecture remains conceptually stereotomic; it is originated in the mass and from the mass, and it’s time after time dug, cut, fractioned in big formats, being conceived anyhow as architecture of gravity and delimitation; the assertive purity of his constructions – even if elaborated for lightenings, entailments or perforations – has always been clearly readable in the net standing of filled solids or empty prisms.

Also the stone chamber of “La Idea Construida” is bringer of all the characters described above; temporary work of little dimensions but not less complex than the Spanish architect’s other permanent works, it is instead thought as a dense synthesis of its compositional poetics; the total and blinding white of Campo Baeza’s buildings gives place to the tints and the material textures of the marble, and light in its various manifestations – horizontal, vertical, oblique – is more than ever “supreme principle of architectural structure and space qualification”.

The interior of the pavilion signed by the slow passage of luminous flows on the surface of marble. (ph Giovanni De Sandre)

An antiquarium for the contemporary design

If museums have a closed and controlled physical dimension, punctuated in a rational and sequential way, the antiquarium – indoor or outdoor – can have an open structure configured more as an aesthetical event than as a syntactical narration.2

Sparse fragments form different ages are disposed in an antiquarium, generally as a wall setting; parts of sculptures, plates in relief, architectonical elements removed from ruins or collected in archaeological expeditions, find their own place of conservation, in front of which the visitors can taste a privileged relationship with unusual finds that he otherwise couldn’t have the occasion to see.

Accumulation and redundancy are indeed the keywords in order to comprehend the concept of antiquarium as a dispositive depositary of memory, as storage of the stratifications of recalling, multiple relays of objects that are disposed in varied, crossed or inverted series.

More than for its museographical project, the antiquarium is interesting for us for its strong significance of perceptive experience focused on the vision of details in a palimpsest of elements, through which the activation, even occasional, of figural, typological and symbolic relationships based on analogy or contrast can be realised.

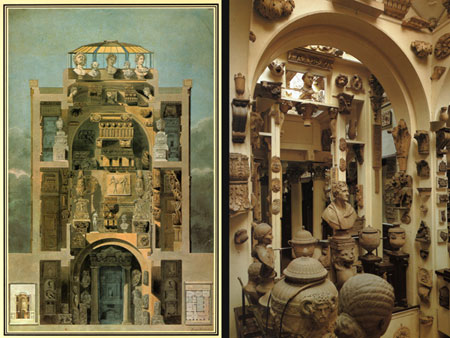

Section and view of the antiquarium at John Soane’s house in London.

As a exhibitional style linked to cultivated collectionism but also to merchants’ interest in the commerce of art pieces, the antiquarium started to spread during the 17th century and reached the peak of its diffusion between the second half of the 18th century and the first decades of the 19th, with the affirmation of classicist and historicist culture in the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Italy, and successively in the United States. Emblematic example of this apogeal moment is the antiquarium at John Soane’s house museum in London, realised by the English architect and archaeologist between 1808 and 1837.

Soane’s consistent antique collection, that contains original finds but also numerous reproductions in chalk, covers the walls of different rooms of the house concentrating in the double-heighted big space of the Dome, projected exclusively to spectacularly accept the core of the antiquarium collection.3

In the dense and apparently confused commixture of pieces, everything is calculated according to criteria of dimensional and proportional assonances: the architectonical elements don’t follow the dispositions they had had in the original buildings because of exigency of composition and symmetry; sculptures aren’t disposed in chronological order because of the will of creating an astonishing horror vacui, in an emotional setting that must be appreciated not only for the preciousness of the single elements composing it but also for the visionary and poetical intensity of the ensemble.

Soane’s masterpiece allows us to fully reach the value of the antiquarium as a powerful instrument of visible communication susceptible of multiple compositive, geometrical or materic interpretations; Alberto Campo Baeza distils the traditional characters of this expositive implant in ‘La Idea Construida’ pavilion, creating a mosaic of antique and contemporary pieces perfectly equilibrate in shapes, proportions and chromatics.

Details of the antiquarium designed by Alberto Campo Baeza for Pibamarmi pavilion at 2009 Marmomacc. In evidence, next to design elements in marble, the historical casts lent by Accademia di Belle Arti in Firenze. (ph Giovanni De Sandre)

[photogallery]acb_album[/photogallery]

He fully valorises the historical casts and the contemporary design elements, selecting and disposing them in a harmonic palimpsests according to a sapient dialectics of contrasts and assonances contaminating sculptural arts, craftwork and design; for Baeza, the incursions of the Antique in the Contemporary, and vice versa, materialise with immediacy and evidence the dimension of Time, basic principle – as seen before – of his architectonic poetry.

The pieces of marble design transmit once again the idea of substantial massivety; their elementary solids are deliberately animated by minimal asymmetries and by incorrect oblique axes; their surfaces are accurately textured and put together smooth and silk-like drafts with rough and veined developments. An Etrurian antefix, a metope from the Parthenon or Hercules’ vigorous and sensual torso present full masses and deep cavities, more or less profound reliefs of limbs, drapes, vegetal ramifications.

Thanks to this unusual and suggestive figural world, and sublimating the aesthetical performance, the architect leads the exhibition choice to a subtle and merely visual syntactical game, made not of chronological succession or symbolical recalls, but uniquely imbued with links between plain or linear shapes and full-relief volumes, with chiaroscuro gatherings and rarefactions of lights and colours: in this way, with the sobriety and the refinement that have always characterized him, Campo Baeza demonstrates that, for such a project of contemporary setting, the antiquarium is the only possible choice.

Notes

1 Alberto Campo Baeza, La idea construida (1996), cit. in Antonio Pizza, “La ricerca di un’architettura astratta. Alberto Campo Baeza” p. 12, in Alberto Campo Baeza. Progetti e costruzioni, Milano, Electa, 2000, pp. 173.

2 See the considerations about this in Pier Federico Caliari, Museografia. Teoria estetica e metodologia didattica, Firenze, Alinea, 2003, pp. 231. In the same volume there’s a critical essay on John Soane’s house museum, recalled later in this text.

3 For an approach to John Soane’s work see: John Summerson, David Watkin, Tilman Mellinghoff, John Soane, Londra, Academy Editions, 1983, pp. 123; Margaret Richardson, Mary Anne Stevens (eds), John Soane architetto 1753-1837, exhibition catalogue, Milano, Skira, 2000, pp. 317.

Go to:

Alberto Campo Baeza

Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze

Pibamarmi